Curtis Fowlkes, whose vital and malleable trombone playing was a steadfast feature of New York’s downtown scene — most visibly with The Lounge Lizards, which he joined in the mid-1980s, and The Jazz Passengers, which he co-founded soon thereafter — died on Aug. 31 in a hospice unit at Brooklyn Methodist Hospital. He was 73.

The cause was congestive heart failure, his son, Saadiah Fowlkes, tells WRTI.

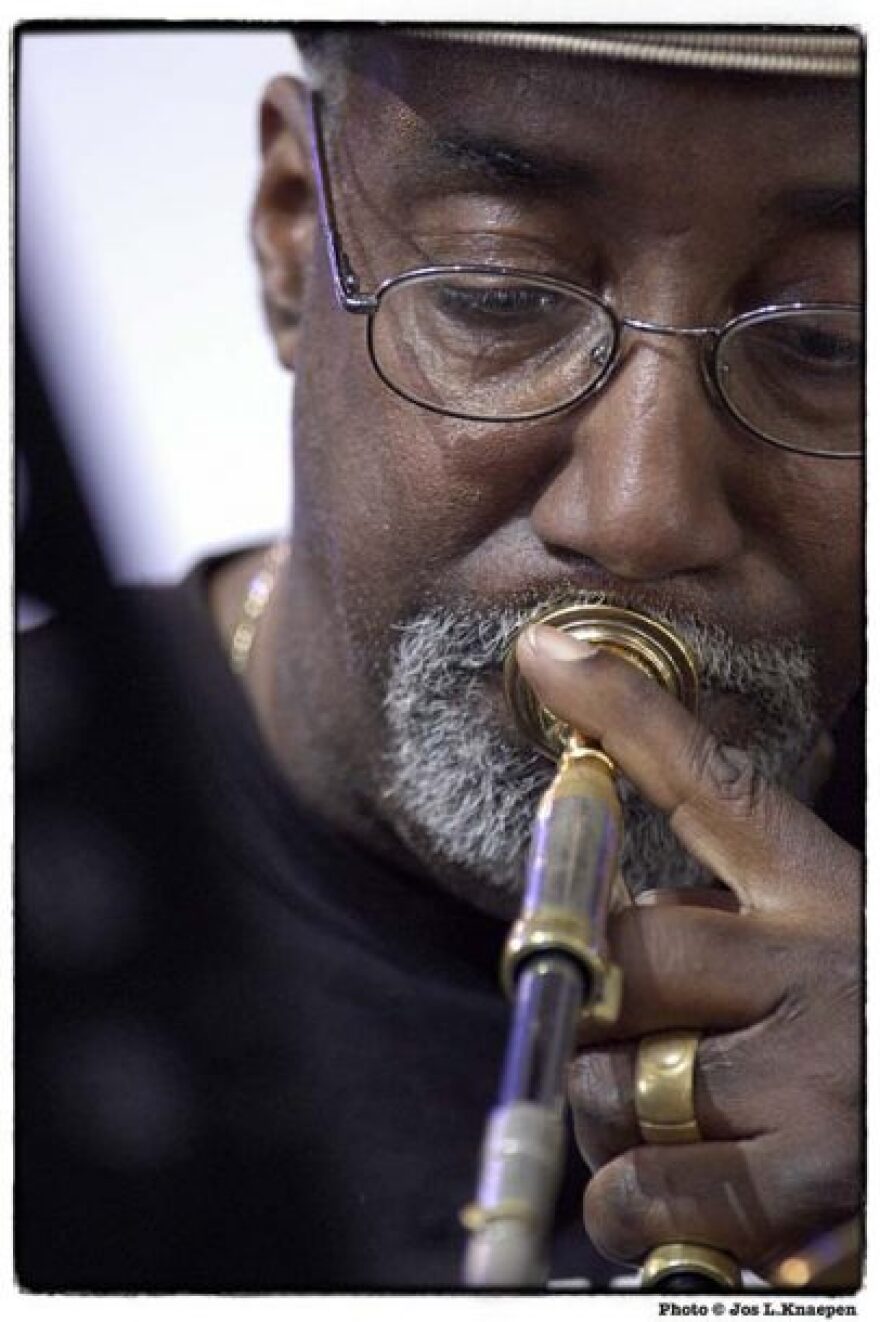

With a tone that could brighten or darken to suit any setting, Fowlkes’ sound on trombone was endlessly supple, and he made his adjustments with no more outward calculation than a treebound chameleon. He was equally at home with boppish fluency or a gutbucket blare, often incorporating the array of lip slurs, wobbles and pitch slides that can make a trombone evoke a human voice. He made use of his literal voice as well, singing with an elegant, low-key flair.

“Curt was one of the funniest, warmest, most insightful people I ever met,” saxophonist Roy Nathanson, his founding partner in The Jazz Passengers, attests in a written statement. “Miraculous really, in the way he could translate that warmth, humor and insight directly into his trombone playing and singing.”

Fowlkes’ versatility and charisma made him a sought-after sideman. He recorded with Elvis Costello, Lou Reed, and the Irish singer-songwriter Glen Hansard, who brought him on multiple tours. He was a vital member of Henry Threadgill’s Very Very Circus and Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra. And he had productive associations with the guitarists Bill Frisell, Marc Ribot, Charlie Hunter and Elliott Sharp, who each featured him on multiple albums, making a space for his rangy composure.

“He was an incredible trombone player,” says trumpeter Steven Bernstein, who enlisted Fowlkes in a number of projects over the years, including his Millennial Territory Orchestra. “And he was a total craftsman. You put a piece of music in front of him and he just played the hell out of it. I never heard him make a mistake.”

Curtis Mataw Fowlkes was born in Brooklyn on March 19, 1950, along with his fraternal twin, James, Jr. Their father, James Roxie Fowlkes, worked as a presser in the garment industry. Their mother, the former Rosa Coor, was a housewife who died when they were 15.

Fowlkes grew up in a Bedford-Stuyvesant brownstone that his grandfather bought in 1921, when there were few other Black families in the neighborhood. He developed his musicianship through a succession of gigs around Brooklyn, where he attended Tilden High School in East Flatbush. He received training through the CETA Artists Project, administered by the New York Department of Cultural Affairs, and during his time at Manhattan Community College.

He circulated as a working musician, holding a regular gig with the Big Apple Circus, where he met Nathanson in the early ‘80s. “It almost makes no sense separating our talking together from our playing together,” Nathanson reflects, “as we both came from Brooklyn, and both shared a similar goofball sense of humor as well as dead serious love of music, jazz, Brooklyn history and any kind of storytelling.”

Fowlkes and Nathanson left the circus to join The Lounge Lizards, which John Lurie had made into an ironical flagship of the downtown scene. “In the process, Curt and I developed a musical language that corresponded with our relationship and eventually we felt we should start a band of our own,” Nathanson writes, recalling the start of The Jazz Passengers in 1987.

Reviewing that group for the New York Times the following year, Jon Pareles characterized its sound as “that of a densely dissonant hard-bop band, updating Charles Mingus’ Jazz Workshop groups, Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers and some of Bobby Hutcherson’s and Eric Dolphy’s 1960s Blue Note albums. But the set also included a version of ‘Do Nothing Till You Hear from Me,’ sung by Mr. Fowlkes with answering riffs from the band.”

The Jazz Passengers — also featuring vibraphonist Bill Ware, bassist Brad Jones and drummer E. J. Rodriguez — released almost a dozen albums, most of them in the 1990s. A reunion in the 2010s, heralded by an album titled Reunited, brought them back into active circulation, often in alignment with guest vocalist Deborah Harry, the lead singer of Blondie. But the rapport between Nathanson and Fowlkes was always foregrounded. “The fact that Curt and I could basically finish each other’s jokes carried over into the uncanny way our horns could pass off phrases to each other, as if we were actually sharing breath,” Nathanson says.

Fowlkes’ marriage to the former Cynthia Lewis ended in divorce last year. Along with his son and his brother, he is survived by a daughter, Elisheba Fowlkes-Dele, and three grandchildren.

As a token of his commitment to collaboration, and perhaps his ultimate calling as a sideman, Fowlkes only released one album himself: Reflect, on Knitting Factory Records in 1999. Largely featuring his own music, it captures his feel for ensemble interplay.

Fowlkes’ heart condition was congenital, and he had been struggling for some time; a GoFundMe campaign was established last month, to support his care. Even as his health faltered, he kept playing and recording music.

He can be heard on a recent series of albums by the Millennial Territory Orchestra, including Popular Culture (Community Music, Vol. 4), released last year. In December he took part in a final, forthcoming Jazz Passengers album.

His son says that he will be remembered as both a committed family man and the ultimate road musician. “His retirement plan was to die on the stage,” says Saadiah Fowlkes. “But more importantly, he lived on the stage.”