“Let us now see what love can do.” — William Penn

These words from Philadelphia’s illustrious founder, a Quaker leader, would guide the composer Romeo Cascarino throughout his life, informing the creation of his magnum opus, William Penn. Written over the course of 20 years, the opera was the composer’s sole foray into the genre, staged at Philadelphia’s venerable Academy of Music in 1982 — the same year as a citywide celebration of Penn and his indelible influence. But despite this major splash late in his career, many people are still unaware of the virtues of Cascarino, a relatively obscure voice in American music. Penn continues to be more familiar, by an order of magnitude, than his admiring acolyte.

Born on Sept. 28, 1922, Cascarino began composing early, and attended South Philadelphia High School, affectionately known today as the “School of the Stars.” His wife, Dolores, characterized him in a recent interview as shy and self-taught at the time. But Cascarino made a favorable impression — notably on the American composer Paul Nordoff, who called him “a genius” and introduced him to the poet, e.e. cummings. Nordoff helped his protégé obtain a scholarship to the Philadelphia Conservatory of Music, and sometime around 1941, Cascarino’s father sent some of his music to Aaron Copland, who invited the young composer to come to Tanglewood.

A few years later, Cascarino won two Guggenheim Fellowships in composition — the first in 1948 for a body of work completed before he was 20, and the second in 1949 for Prospice, an orchestral ballet. These achievements set the stage for 1950, when Cascarino became chair of composition at Philadelphia’s Combs College of Music. At that time, Combs was known for its faculty, including pianists Toni and Rosi Grunschlag, and organist Keith Chapman. As another measure of the school’s stature, notable Combs alumni included composer Vincent Persichetti, pianist Leopold Godowsky, author and music therapist Gail Levin, and saxophonist John Coltrane.

Dolores Cascarino, a soprano who studied with Licia Albanese, was happy to add more information on her husband’s background at Combs, where they met in 1956, before marrying in 1960. He wrote “Little Blue Pigeon” (1957) for her, based on “Japanese Lullaby,” a poem by Eugene Field, and the result is a delicately phrased song with a nostalgic, Hollywood glow, which Cascarino later included in Eight Songs for Voice and Piano (1939, 1957).

Dolores recalled Marguerite Barr, head of Combs’ vocal studies, who was aware of the composer’s background and reputation. “She knew that the president of Combs, Helen Braun, was looking for a theory and composition head, so Barr introduced them. But at the time, he was not interested in teaching.” Nevertheless, Cascarino accepted the position, assuming it would be temporary; he ended up staying until 1990, when the school closed.

Cascarino was a formidable pianist. On the 1963 Columbia recording of his Sonata for Bassoon and Piano (1947) — commissioned by Sol Schoenbach, former principal bassoon of the Philadelphia Orchestra — Cascarino is at the keyboard. (The recording appears in a 2017 celebration with Ross Amico of WWFM, marking the composer’s 95th birthday.)

Dolores recalls, “He had amazing ability, including accompanying opera performances during his time at South Philadelphia High School, mostly self-taught in piano, like everything else he learned. Sometime in his teens, he studied classics in New York with pianist and educator Adele Margulies (1863-1949). He had a photographic memory, often studying his music during the bus ride to New York.” A true autodidact, he was an obsessive reader, and would often fall asleep investigating musical scores. He also taught himself Greek. Dolores would pick up books on the language for him at New York’s famed Rizzoli bookstore, and he taught himself so thoroughly that he was able to write letters to an old Army friend from Greece, whom he met during World War II.

Much of Cascarino’s work was completed in the 1940s and ‘50s, and bears an unmistakable mid-20th-century stamp, evoking strains of Copland, Bernstein, or Samuel Barber. In Fanfare, Eric J. Bruskin commented: “By not trying to be profound, he manages to avoid writing the kind of pedantic, grey music that makes the music of many mid-century Americans more dutiful than beautiful.” Dolores waxes nostalgic about his omnivorous mind: “He would hear harmonies in the bells at City Hall.”

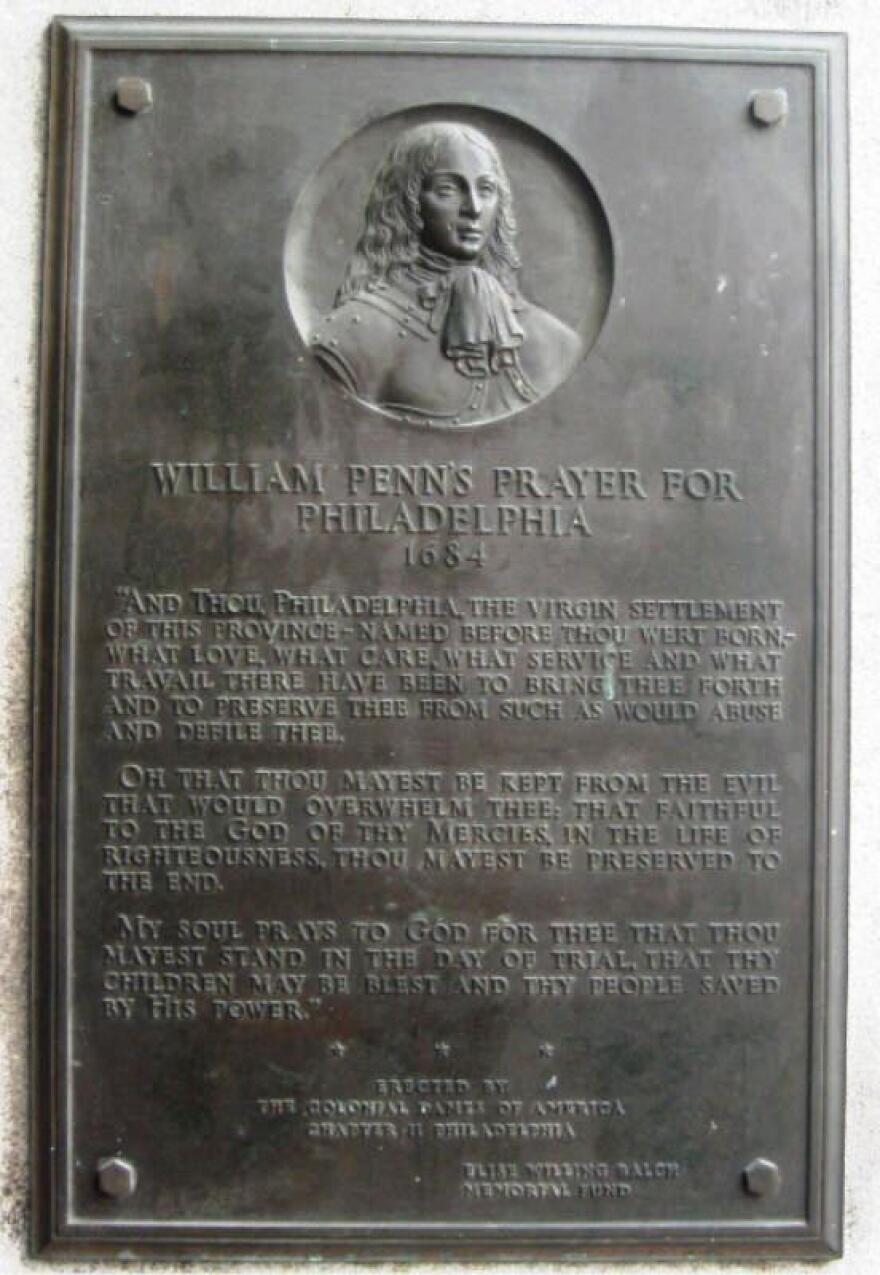

Philadelphia’s City Hall was the genesis of William Penn, which was conducted by Christopher Macatsoris, with renowned bass-baritone John Cheek in the title role and Dolores as Gulielma Maria, Penn’s first wife. As a boy, Cascarino was enchanted by the plaque in the City Hall courtyard, with Penn’s prayer for Philadelphia from 1684.

Two early choral works inspired the opera: Prayer for Philadelphia (1950) and The Treaty (1953), inspired by Penn’s 1682 Treaty of Shackamaxon. In Act I, Scene 2 (heard during the Amico interview above), Penn and Gulielma plan the creation of Philadelphia, with Cheek and Dolores intertwining in appropriately majestic form.

Despite his obvious gifts, Cascarino will be new to most listeners. For curious ears, the best starting point might be the 2006 sampler on Naxos American Classics (8.559266) with four orchestral works: Pygmalion (1954), Portrait of Galatea (1950), Prospice (1948), The Acadian Land (1960, based on Longfellow’s Evangeline) and Blades of Grass (1945), all with the Philadelphia Philharmonia conducted by JoAnn Falletta. Longtime Philadelphia writer and critic Tom DiNardo — who wrote for The Daily News and The Inquirer, and was a champion of Cascarino’s work — served as executive producer of the recording. Dolores adds, “This was the first time many of us had heard them performed.”

She mentioned some personal favorites: Pygmalion, a ballet enveloped in a sensuous haze, and The Acadian Land, equally lush, peppered with woodwinds — and of course, William Penn. (“We just say ‘the opera’ in my family.”) And given the dearth of recordings, the sound, captured at the First Presbyterian Church in Germantown, allows the composer’s phrases to bloom more fully. In the end, his pastoral tranquility wins the day; he might be a transatlantic soulmate to British composers Frederick Delius or Ralph Vaughan Williams.

In 2011, a second version of Blades of Grass appeared with the Orchestra 2001 (Innova #745) on an album titled To the Point, with Dorothy Freeman in the poignant English horn solo. (Freeman’s husband, James, founded the ensemble.) The recording places Cascarino in the company of other works by Jennifer Higdon, Andrew Rudin, Gunther Schuller, and Jay Reise.

But many of Cascarino’s other creations have yet to be recorded, especially his chamber music. Some of these include Paraphrase for bassoon (1986), based on Mozart’s Overture to The Marriage of Figaro; a 1985 transcription of Portrait of Galatea for violin, cello, and piano; a 1952 two-piano reduction of Prospice; and The Towpath (1984), a woodwind sextet inspired by the trail in New Hope, Pennsylvania.

Over the years, Cascarino’s works have been performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra, New Orleans Philharmonic, Royal Philharmonic of London, and the Nord Deutsches Symphony, among others. In January 2023, Emily Ray will conduct Prospice (inspired by Robert Browning’s poem) with the Mission Chamber Orchestra of San Jose. Two months later, in March, Beverly Everett — who previously led Pygmalion with the Bismarck-Mandan Symphony Orchestra — will conduct Minnesota’s Bemidji Symphony Orchestra in The Acadian Land.

It's a testament to the quality of the work that Cascarino's music continues to find interpreters, even if those moments are few and far between. His centennial provides the ideal opportunity to remember him — and a welcome invitation for anyone inclined to discover, musically, what love can do.