Niccolò Paganini, the sensationally gifted violinist, entered this earthly plane on Oct. 27, 1782. His birthday, falling as it does in the midst of spooky season, provides a perfect excuse to delve not only into his musical canon but also the darker currents swirling about his legacy. As many listeners are aware, Paganini was dubiously described in his time as a sorcerer, a charlatan, even a demon; he was said to have struck a deal with the devil. Today he’s remembered by a juicy sobriquet, “The Devil’s Violinist.” What could possibly be a more irresistible musical icon as the hours creep toward Halloween?

Paganini was a child prodigy in his native Genoa, Italy — taking up the violin by age 6 or 7, and soon embarking on a course of study with some of the instrument’s finest practitioners, including Alessandro Rolla. “But already this genius, who was destined to effect a revolution in his art, was unable to submit to the established forms of the schools which had preceded him,” observed a New York Times article published in 1871, just over 30 years after his death. The mystique of Paganini’s virtuosity, and the occult-like intensity of his studies, fed into Mephistophelean perceptions of his work — at least, this was the case from 1814 on, after a three-year period that one biographer, Geraldine De Courcy, characterized as his “wastrel years.”

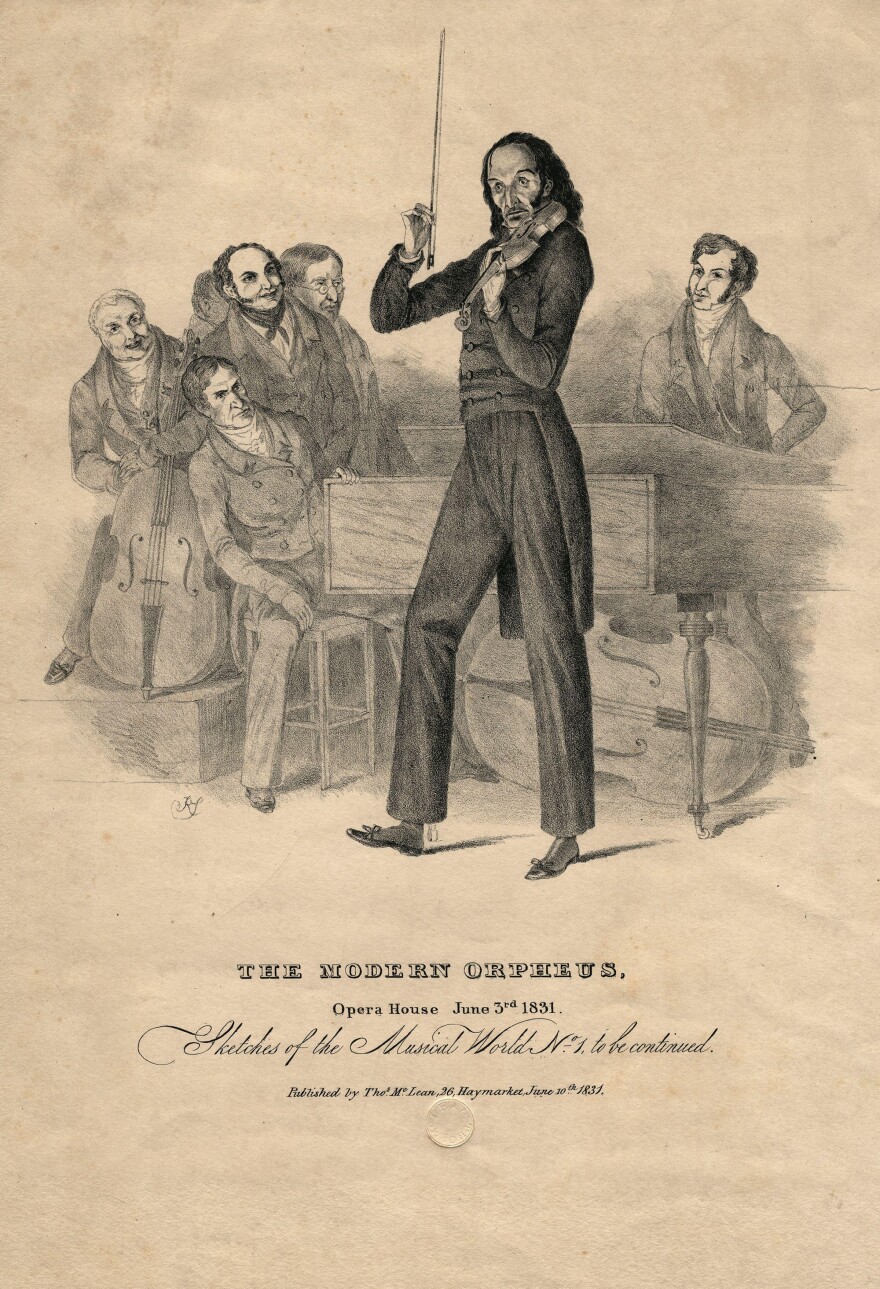

Every Lucifer should look the part, and Paganini certainly did: tall and gaunt, with unusually long fingers and hyperextensible joints (the result, it’s long been speculated, of the genetic disorder Marfan syndrome). He exuded the magnetism of a conjurer, making expressive use of advanced bowing techniques — like spiccato, left-hand pizzicato, and saltato — that would become part of the standard toolkit for violinists. By all accounts, Paganini was also a flamboyant showman. David Garrett, the German crossover-classical star, brought this uncorked gusto to his portrayal in the 2013 biopic The Devil’s Violinist — a film dryly appraised by the Times as “so magnificently misjudged that it almost defies description.”

Musicologist and violinist Maiko Kawabata, in her 2013 book Paganini: The ‘Demonic’ Virtuoso, sets a broader context for the devilish discourse around her subject: “Various cultural currents in early nineteenth-century European society provided multiple settings for Paganini’s identity as a ‘demonic’ figure to proliferate: the popularity of Goethe’s Faust and the cult of Byron highlighting post-Enlightenment secularism, the resurgence of interest in the middle ages, the breaking of sexual taboos, the rise and fall of Napoleon, and the birth of capitalist enterprise.”

That’s a lot to take into consideration. For the moment, we needn’t look much further than the music, whose spellbinding properties are powerfully intrinsic. Paganini composed concertos, sonatas and chamber music, but the heart of his contribution to the classical literature can be found in his 24 Caprices for Solo Violin, a series of études first published in 1820, and developed over the previous two decades.

The Caprices have been extensively recorded since 1940, when the Austrian violinist Ossy Renardy took a crack at them for RCA Victor. According to WRTI’s Zev Kane, the gold standard is Itzhak Perlman’s version, released 50 years ago on EMI: “Romantic passion and technical panache in perfect balance.”

Kane also endorses a version from 2022, by Ning Feng: “Sensitive, nuanced, and deeply attuned to virtuosity as a philosophy rather than a mere activity.”

Another recent release, The New Paganini Project, marks the debut of violinist Niklas Liepe with the German Radio Philharmonic of Saarbrücken / Kaiserslautern. “I have always regretted the fact that in the concert hall the caprices have not been able to enjoy the attention that, in my opinion, they deserve,” writes Liepe in his notes. “They are much more than pure ‘technical studies.’ Right up until today each of them has remained a small jewel for every violinist. The main idea of my project is, by adding a symphony orchestra, to provide these small jewels with a new ‘setting and precision polish.’”

Paganini lore also extends beyond classical circles, as many jazz fans will recall. In 2001, Regina Carter had the opportunity to perform and record with Paganini’s legendary 1743 Guarneri violin, known as Il Cannone (“The Cannon”). This encounter — the first time the instrument had been entrusted to a jazz musician — later yielded an album on Verve: Paganini: After a Dream. (The closest she comes to acknowledging Paganini’s darker legacy is the inclusion of a Luiz Bonfá song from Black Orpheus, which invokes the Greek myth of the underworld.) As Carter told NPR around the album’s release: “When you look back at Paganini’s history and the era that he came out of, he was a Baroque musician, and Baroque musicians improvised."

But it was another Verve artist who established the most familiar connection between Paganini and jazz. The First Lady of Song, Ella Fitzgerald, made her original recording of “(If You Can't Sing It) You'll Have to Swing It (Mr. Paganini)” on Oct. 29, 1936. It became a staple of her repertoire; here she is performing it on the Ed Sullivan Show in ‘68.

The tune, by Sam Coslow, is a puckish confection that draws less on the specifics of Paganini’s story than on a generalized notion of longhair formality — in clear contrast to the freewheeling spontaneity of jazz, made manifest in Ella’s scat syllabics. (And in the lyrics, which at one point rhyme “Mister Paganini” with “Now, don’t you be a meanie.”)

In any performance of the song, Fitzgerald sounds both supremely in command of her instrument and swept away by the moment — a characterization with certain parallels that should be implicit, if you’ve read this far. As they say, the devil’s in the details.