The musical career of 19th-century American guitarist Justin Holland describes a contradictory balance of notability and obscurity, a life both seen and unseen. At a time when the classical guitar was ascendant as a parlor instrument, he was its most prominent teacher and proselytizer, the author of two method books that effectively set the standard. Holland’s Comprehensive Method for the Guitar, first published in 1874, was the best-selling American music publication of the 19th century.

“His work was extremely significant,” observes Christopher Mallett, a leading Holland scholar of our century, in a recent interview for the Austin-Marie Collection. “I would even say that he was a household name to most amateur guitarists, which is amazing to me. And many of them, including his publishers, didn’t know he was Black.”

Mallett, a Bay Area guitarist and educator most widely known as one-half of the celebrated Duo Noire, has devoted a great deal of time and effort to excavating Holland’s music and life story. Much of that legacy now resides either in the music division of the Library of Congress or at Cal State Northridge, in the form of solo song and dance arrangements. They form the basis of Mallett’s sensitive and impeccably played new album, Justin Holland (1819-1887): Guitar Works and Arrangements.

Holland was born free in Norfolk County, Va., a farmer’s son who showed musical talent at an early age. At age 14 he relocated to New England, where he had a formative encounter with the Spanish guitarist Mariano Perez, and studied with members of Ned Kendall’s Boston Brass Band. His next training ground was at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music, where he later established a foothold as an educator — following a pilgrimage to Mexico to learn Spanish, the better to grasp the instruction of European guitar masters Dionisio Aguado and Fernando Sor.

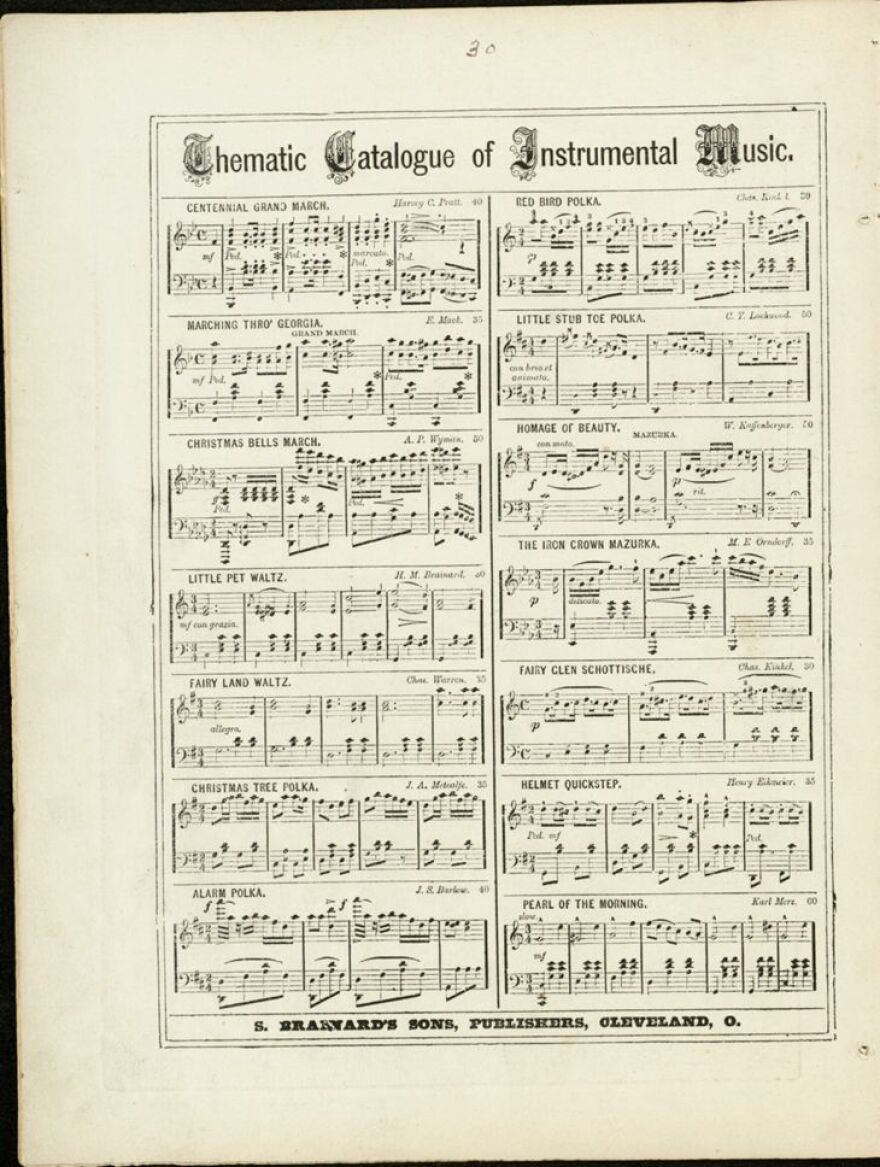

From 1848 on, Holland published a considerable volume of sheet music: some 35 original compositions and 300 arrangements of operatic themes from the European canon and popular songs in the American grain. Mallett’s album includes a jaunty Holland original, “An Andante in C Major,” as well as a varied assortment of arrangements: folk dances of Polish or Scottish origin; the popular “Spanish Fandango,” in an open G tuning; even a college fight song, “Delta Kappa Epsilon March,” which appears here in its first known recording.

Mallett’s resonant tone and delicate touch, which he supports with a breath-like sense of phrase, serve this music extraordinarily well. He has the resources to bring an orchestral fullness to Holland’s arrangements, especially on an incident-rich piece like “Stephanie-Gavotte Op. 312,” which elaborates on a French folk dance. A pair of Mazurkas sequenced side-by-side on the album, “Antoinette Polka Mazurka” and “Pearls of Dew,” inspire an elegant but also energetic reading; on the latter in particular, Mallett intersperses a flowing cadence with one staccato line that’s almost startling in context, as if to keep a dance partner on her toes.

At times, Mallett also seems to acknowledge the humbler side of Holland’s legacy. The composer built his earliest musical foundation in the African American church, and his reverence can be heard in a reading of the hymn “Nearer my God to Thee.” Mallett begins another American standard, “Home Sweet Home,” at a slow, even halting tempo, as if to identify with the generations of homespun guitar hobbyists who carefully picked their way through Holland’s notation. (After one full pass through the form, Mallett opens up, moving into a more fluent and elaborative mode.)

It wouldn’t be accurate to suggest that Holland willfully or strategically “passed” as white in the service of his publishing success: in fact, he was a tireless advocate for the rights of Black Americans, providing crucial assistance with the Underground Railroad and serving as an officer in National and State Negro Conventions.

Still, the restrictions of the age surely influenced Holland’s decision to focus on teaching and publishing rather than a performing career. He never achieved the kind of spectacular fame later claimed by someone like Andrés Segovia. And because his career predated the widespread availability of recording technology — he died just a decade after Thomas Edison invented the first phonograph — Holland was consigned to the historical record, when he was remembered at all.

What’s so rewarding about Justin Holland (1819–1887): Guitar Works and Arrangements is the way Mallett breathes life into the ledger lines, showing how that historical record can yet become an unfolding reality. He isn’t merely shining an overdue light on Holland’s singular achievements, but also reminding the rest of us how indebted we are to that legacy — and how beautifully it still moves today.

Justin Holland (1819–1887): Guitar Works and Arrangements is available now on Naxos; order it here.