“I am Count Dracula. I am really the bebop vampire.”

So intones Philly Joe Jones, in a comically thick mock-Transylvanian accent, near the top of his 1958 debut as a leader. He’s doing what had become a trademark piece of stage patter: imitating Bela Lugosi, who’d played the iconic title role in Dracula.

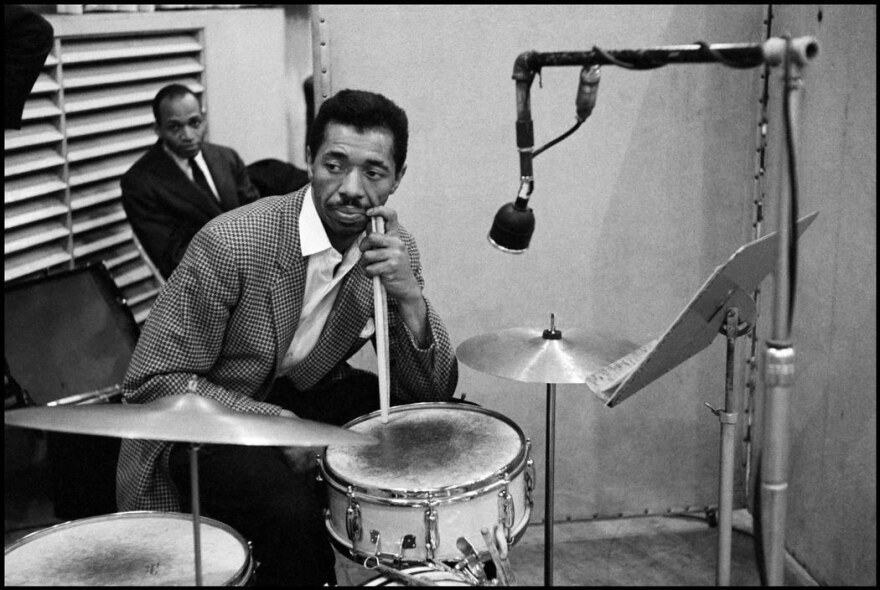

The extended bit — which at one point finds Philly Joe’s Count Dracula exhorting his children to “drink your soup, before it clots,” and to “bite your Mama goodnight!” — has a Borscht belt camp that you don’t often hear on a modern jazz recording. The novelty extends to the cover photo, featuring a vampire, eyebrows arched, lurking behind a snare drum. Of course the title of the album and its opening track is “Blues for Dracula,” and it has been a staple of Halloween compilations and playlists ever since — as ageless as its inspiration, and nearly as shrouded in mystery. How did it come to be?

First, it must be said that Philly Joe Jones stood within the first tier of jazz drummers in New York in 1958, as a member of the Miles Davis Sextet and a busy freelancer on the scene. That July, he’d played on Porgy and Bess with Davis and an orchestra conducted by Gil Evans. In August he had recorded the Riverside albums It’s Magic, with Abbey Lincoln, and It Could Happen to You, with Chet Baker.

It was Riverside that set up Philly Joe with his own recording session on Sept. 17, 1958, at Reeves Sound Studios. He had the luxury of an ace band with Nat Adderley on cornet, Johnny Griffin on tenor saxophone, Julian Priester on trombone, Tommy Flanagan on piano, and Jimmy Garrison on bass. His producer was Orrin Keepnews, an astute session veteran and the co-founder of Riverside Records.

“I’m sure that the Bela Lugosi imitation was Philly Joe’s idea, but I suspect that my father didn’t require a lot of persuasion,” says Peter Keepnews, a New York Times editor and standup comic. “The album was of course Philly Joe’s first as a leader, and I imagine Orrin was amenable to any gimmick that might help generate attention.”

By and large, Philly Joe had little trouble in that area. Historian John Szwed notes in his biography So What: The Life of Miles Davis that after Jones left Philadelphia for New York in the late 1940s, he “worked his way through the clubs, strip houses, and dance halls. He could dance, do dialect bits, and mimic anyone. His Dracula routine epitomized what was becoming known as sick comedy (‘Shut up and drink your blood’). Lenny Bruce was always cracked up by it and worked his own version into his act.”

The flow of that influence could have run the other way, given Bruce’s cultural sway at the time. What’s certain is that he and Philly Joe formed a mutual admiration society, and each was paying close attention to the other. “Philly Joe says hello,” Bruce quips, as an apparent ad lib, toward the end of “Religions, Inc.,” from his 1959 album The Sick Humor of Lenny Bruce. Also in 1959, he hosted a television special called The World of Lenny Bruce, on which he brandished an LP copy of Blues for Dracula, and then interacted with a band led by Cannonball Adderley, and featuring Philly Joe.

Keepnews is among those who believe that Jones’ comic bit has some Bruce in the bloodline. “One thing I know about ‘Blues for Dracula’ is that Philly Joe wasn’t really imitating Bela Lugosi,” Keepnews tells WRTI, in an email. “He was imitating, or trying to duplicate, Lenny Bruce’s imitation of Bela Lugosi.”

Whatever the case, “Blues for Dracula,” a minor blues credited to Griffin, delivers more than just spooky laughs. As the music fades up from the voiceover, there’s room for a succession of solos by Priester, Griffin, Adderley and Flanagan. The horns then restate the melody before the Count reemerges from his coffin. “Oh, what are you doing here with the children again?” he barks. “Children, go in the belfry and play with the bats!”

From that point on, Blues For Dracula abandons its arch premise, and becomes a top-flight hard-bop session, with steadfast mastery across the board. There’s a lively Latin-jazz composition by Cal Massey (“Fiesta”). There are bebop standards by Davis (“Tune Up”) and Dizzy Gillespie (“Ow!”). Jones steers the action throughout with his evercrisp ride cymbal and a briskly annotative snare drum. It’s his session, and all jokes aside, he’s firmly in control.

But that’s not to imply he ever left his vampiric shtick behind. “He used to do that bit all the time,” recalls Sumi Tonooka, who played piano with Jones in the mid-1970s. “He had his Bela Lugosi imitation, and I think he imagined himself as a comedian. I remember one gig that we did, my first time in D.C. working with him. The bass player got sick, so he was late getting to the bandstand, and during the first set, Philly just told jokes for maybe 20 minutes before we started playing. I don’t know if the club owners were thrilled about that, but the audience seemed to enjoy it.”

Whether the humor of “Blues for Dracula” lands with a listener today is totally subjective, and maybe beside the point. The point is that through unabashed novelty, seasonal applicability and force of personality, this is an album we’re still talking about more than 65 years after its release. And in the spirit of the gag, you have our blessing to appraise Blues for Dracula as follows: “Philly Joe Jones’ first album? Yeah, it sucks.”