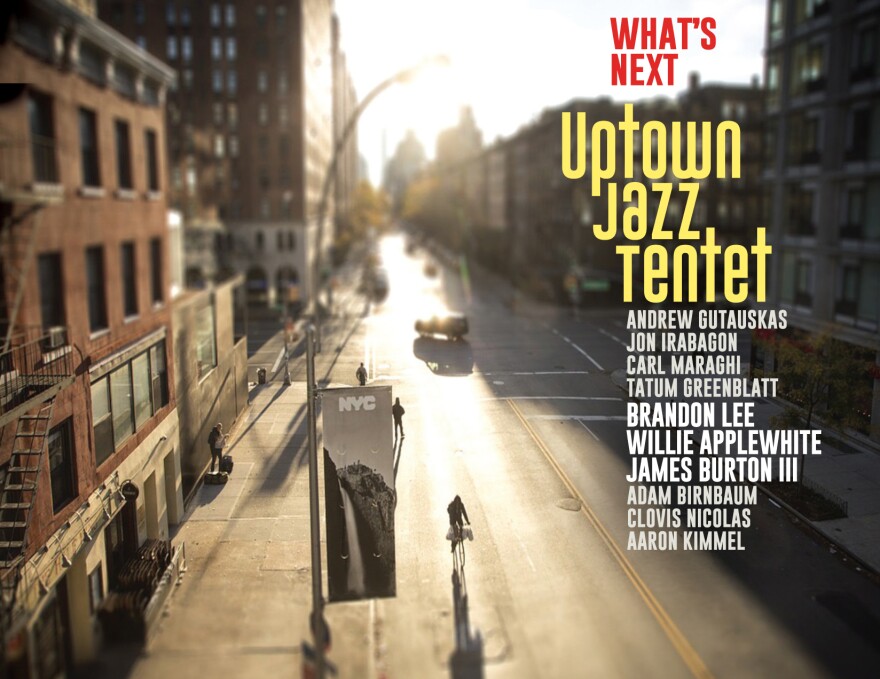

November 2, 2020. In light of Election week and 2020 in general, the title of the Uptown Jazz Tentet’s (UJT) new album, the follow-up to their 2017 debut There It Is, is perfect: What’s Next. Weary cynicism, steely resilience, forward-thinking resolve, stubborn optimism—that album title says it all in two simple words.

But UJT’s powerful, sophisticated, and relatively understated approach extends beyond pithy album titles. The substance of What’s Next—ambitious, often incendiary arrangements of compositions by Wayne Shorter, Milt Jackson, Kenny Barron, and Duke Ellington, and originals inspired by Junior Mance, Ornette Coleman, Joe Henderson, and Dizzy Gillespie—is what makes it a worthy addition to your record collection.

What’s Next opens with “Uptown Bass Hit,” a clear riff on Dizzy Gillespie’s “One Bass Hit,” composed by trombonist Willie Applewhite, one of UJT’s three co-leaders. Like a young Ray Brown as a Gillespie sideman and Percy Heath as the low-end anchor of the Modern Jazz Quartet, this is bassist Clovis Nicolas’s time to shine. The tune opens with first the full orchestra, and then successively smaller sections, dialoguing with Nicolas before allowing him, accompanied only by a comping Adam Birnbaum on piano, to introduce the theme in full. On the next go-round, Nicolas reprises the theme, and this time is joined in gorgeous unison playing by Carl Maraghi on clarinet and Andrew Gutauskas on flute. Solos follow from Applewhite and tenor saxophonist Jon Irabagon on what is simply a really solid modern bebop arrangement.

The title track, a harmonically sophisticated piece written by another co-leader, trumpeter Brandon Lee, follows. Inspired by tunes like Joe Henderson’s “Inner Urge” and “Black Narcissus,” it also communicates heavy influence from the hard bop anthems of Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers and reminds me most of those legendary Messengers albums—Moanin’, Mosiac, A Night in Tunisia, et. al.— produced by Alfred Lion for Blue Note.

Speaking of Lion and Blue Note, there’s a tune here that might remind you of another immortal, Lion-produced Blue Note recording because, in fact, it’s pulled directly from one. I’m referring to the take here on Wayne Shorter’s “Infant Eyes,” from 1966’s Speak No Evil. It’s one of Shorter’s most beautiful ballads, and when people tell me they can’t get into sax ballads, I use this tune and Coltrane’s “Naima” to change their minds.

Replicating the atmosphere of the original, which exists in such a rarefied air, is impossible. But commend UJT for utilizing its personnel in a way that makes for a very respectable rendition. For as beautiful as the original is, there’s also a forlorn quality, a profound bleakness. Some find great beauty in art that’s able to evoke those feelings; others can’t handle it or don’t want to. For that latter group, this is the version of “Infant Eyes” for you.

Atmospherically, the quality that’s all too generically described as “moodiness” on Speak No Evil is largely absent from this arrangement, another by Applewhite. Whether the slight alteration in mood is purposeful, I can’t help but think that as affecting as Shorter’s playing is on the original, the difference comes down to the presence of Herbie Hancock and Ron Carter on Speak No Evil.

But I digress….

Maraghi plays Shorter’s lead role here, interestingly on baritone sax; he really pulls it off. His baritone offers something different than Shorter’s tenor, and different can be good. In this case it is. His tone is rich and full and reassuring to the extent that Shorter’s was so beautifully desperate. The arrangement is a winner and the saxophone section playing, specifically, offer the musical equivalent of the most welcome signs of relief.

If you can’t get enough of the low notes, check out Maraghi once again on bari sax on the Ornette Coleman-inspired “Brambin.” Or, even better yet, there’s the closer, a James Burton III arrangement of Kenny Barron’s “Voyage” prominently featuring Burton III on bass trombone. This is no simple arrangement and yet the section playing—‘bones, trumpets, and saxes— is so extraordinarily tight and precise. Drummer Aaron Kimmel, who seamlessly pulls off everything thrown his way stylistically but also with respect to the subtle time shifts that permeate the album, gets some deserved, albeit limited, time soloing here.

For more of Kimmel out front (outside the late-night TV context), see Burton III’s Basie-like arrangement of Milt Jackson’s “SKJ.”

“Mance’s Dance,” a boogaloo written for pianist Junior Mance, presents one of the album’s most memorable moments, saxophonically speaking. Gutauskas throws down the gauntlet on alto saxophone before the tune’s composer and arranger, Tatum Greenblatt, responds undeterred with a flurry of his own improvisational brio, on trumpet.

That’s not quite as fierce as the battle that takes place between Greenblatt and section-mate Brandon Lee on Burton III’s arrangement of Ellington’s “In a Sentimental Mood,” Mambo-infused take that may leave you sentimental for a version of the Duke resplendent in his cabana-wear. As the weather gets colder and we turn the clocks back and prepare to see less of the sun for a while, this is a version of the Duke over which no one will blame you for becoming sentimental.