“Finally!” booms the chorus, in the closing movement of Credo. The word resounds twice more, before the payoff: “Finally, Finally, I believe in Patience.”

W.E.B. Du Bois wrote the text, but it was Margaret Bonds, the composer of Credo, who repeated that “Finally” for emphasis, setting it against a dramatic blare of low brass and kettle drums. Bonds knew a thing or two about patience, but she couldn’t have known how prophetic this declaration would be in relation to her work. She lived to hear only one full orchestral performance of Credo, by the Albert McNeil Jubilee Singers in 1967. Zubin Mehta conducted the Los Angeles Philharmonic in a partial premiere of the piece — in 1972, months after her death at 59.

Bonds would surely have been pleased, and probably surprised, to witness the exalted reputation that Credo now holds within the classical and choral repertory. A proud centerpiece of Opera Philadelphia’s new season, it also now has a sterling performance on record by The Dessoff Choirs, a New York chorus whose previous releases include a world premiere in Margaret Bonds: The Ballad of the Brown King & Selected Songs. Now Margaret Bonds: Credo, Simon Bore the Cross brings new luster, and the utmost care of execution, to not one but two of Bonds’ celebrated late works.

Under the baton of Malcolm J. Merriweather, The Dessoff Choirs has a profound simpatico with Bonds’ mature compositional style, a glowing synthesis of African American and European concert music. The chorus is also firmly aligned with the composer’s vision, and the way in which its realization today extends a legacy.

This is as true of Simon Bore the Cross, another piece Bonds never lived to see realized in concert, as it is of Credo. “Both texts reflect Bonds’ belief in racial uplift,” notes Dr. Ashley Jackson, the choir’s eminent harpist, in the album liner notes. “By centering black historical figures and setting words by black writers, she honors the accomplishments of her ancestors and contemporaries.”

Chief among those contemporaries was poet Langston Hughes, who became one of Bonds’ creative partners soon after they met in New York during the peak of the Harlem Renaissance. She set much of his writing to music; Simon Bore the Cross, which celebrates the North African man known in scripture as Simon of Cyrene, was a joint creation completed in 1965. The Dessoff Choirs imbue this work with solemn dignity, no less in a movement like “VII. The Crucifixion” than on the annunciatory Prelude. The deft balance of voices, strings and organ in this recording underscores the depth of Bonds’ orchestration, notably on “III. The Trial,” which alchemizes Middle Eastern scales and Negro spirituals, while largely avoiding the pitfalls of Orientalism.

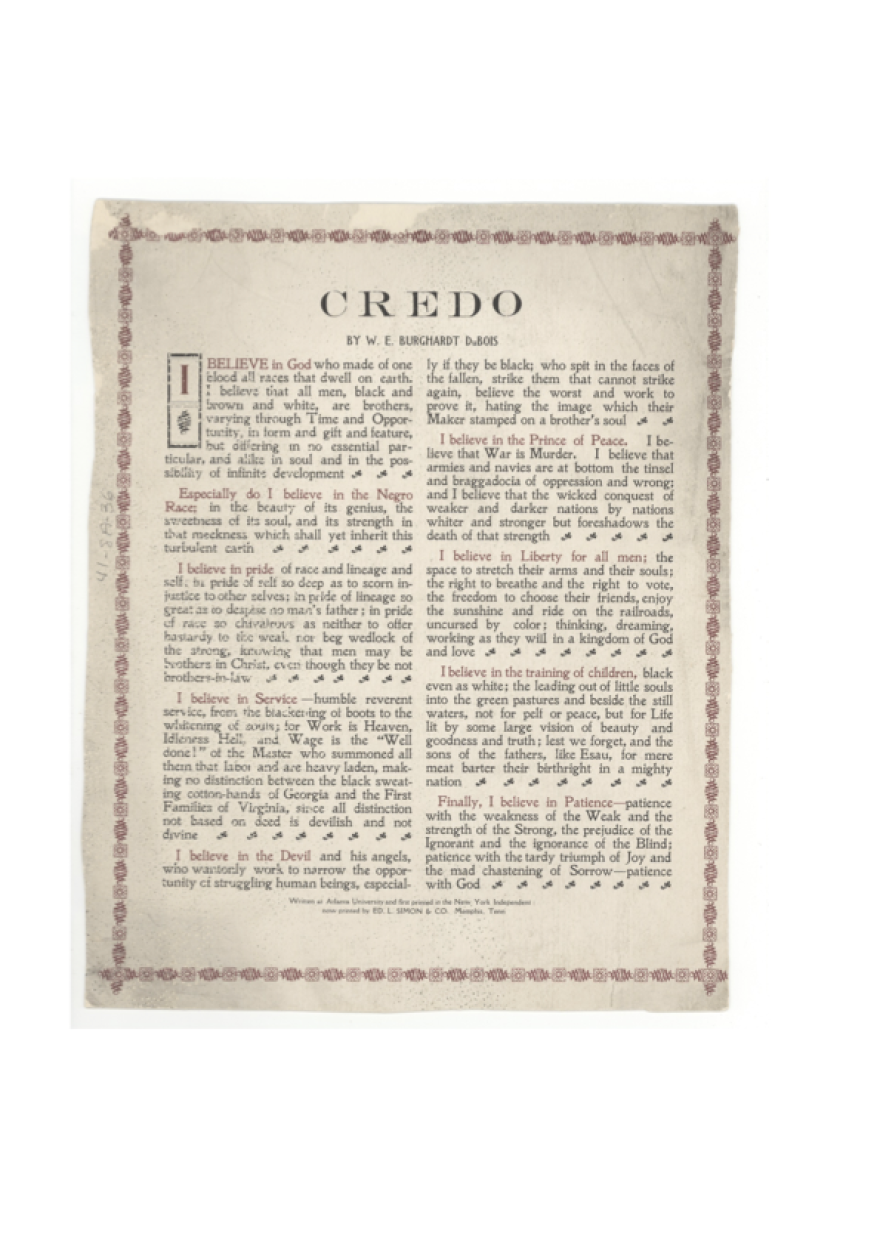

Du Bois’ Credo was first published in The Independent, a New York newspaper, on Oct. 6, 1904. He reprinted it in his 1920 book Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil, which is where Bonds encountered it.

As Bonds scholar John Michael Cooper has observed: “The text is a masterpiece of a strategy of dual-perspective: its verbiage of racial harmony and scriptural imagery of children in green pastures beside still waters — language designed to convince skeptical Whites that Du Bois was committed to a racial harmony founded in the Judeo-Christian institutions that they professed to adhere to — is nestled in a fierce pride of Black lineage and self, condemnation of war, and (most importantly) the overarching thesis that racial equality and justice were not things that were granted by humans (let alone White society) but rather were divinely ordained.”

Taking a cue from Du Bois, each of the eight movements in Credo begins with a statement of belief. The foundational opening phrase, “I believe in God,” bursts out of an anticipatory tremolo like the first rays of daybreak over a gray horizon. Bonds keeps her harmonic movement steady and stately, but with a gorgeous lyrical inflection; the gospel-tinged soprano solo in “II. Especially Do I Believe in the Negro Race,” warmly rendered here by Janinah Burnett, is just one case in point.

Bonds composed with an organic sophistication, smoothing over the seams of her many juxtapositions of musical style. Credo further describes an arc that could only have been painstakingly devised. The hints of parallel harmony in “III. I Believe in Pride of Race” provide a natural lead-in to the piece’s starkest flash of modern dissonance, “IV. I Believe in the Devil.” This in turn flows like a waterway into “V. I Believe in the Prince of Peace,” which finds Bonds at her most luxuriously tonal, courting Romanticism — up until the introduction of the phrase “war is murder,” and a breathtaking ensuing passage: “I believe that the wicked conquest / of weaker and darker nations by nations whiter and stronger / but foreshadows the death of that strength.” The storm subsides, and peace comes back into view, attended by an upswell of strings and a woodland drift of flutes.

Just as Bonds’ soprano soloist heralds “the Negro Race,” a baritone — in this case, a surefooted Dashon Burton — gives voice to “VI. I Believe in Liberty.” The shifting harmony in this movement suggests not a trumpeted manifesto but rather the expression of some noble, fragile aspirations. By the time we reach “VII. I Believe in Patience,” Bonds has taken us through an emotional landscape, exceptional in its dynamic nuance and tonal variation. Strikingly, too, the final movement returns to the A minor key and motivic material of the first movement. This cyclical turn emphasizes both the exhortation and the sublimated pain — ”the tardy triumph of Joy and the mad chastening of Sorrow” — in Du Bois’ final line: “Patience with God!”

The Dessoff Choirs will release Margaret Bonds: 'Credo, Simon Bore the Cross' on Friday; preorder here.