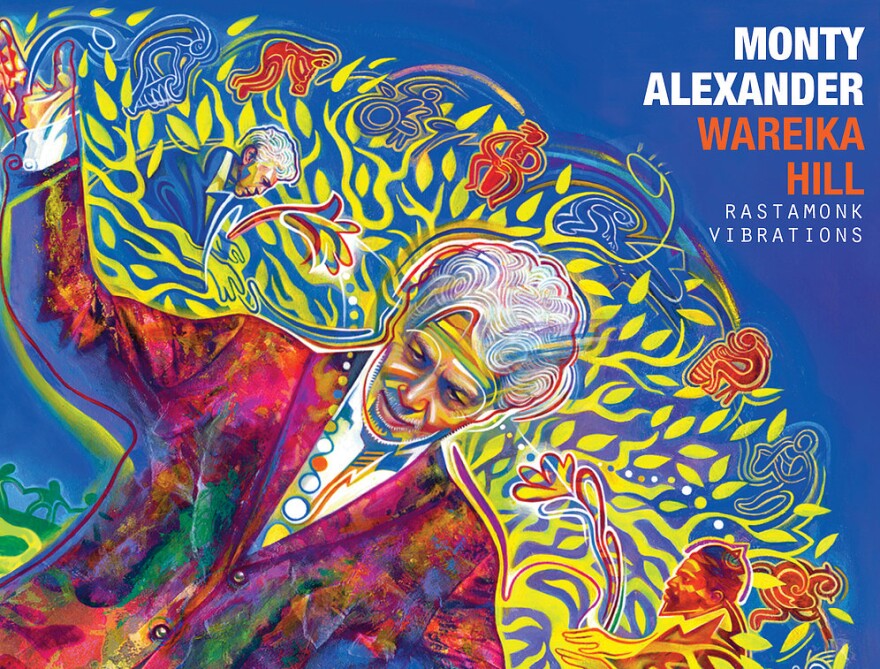

October 7, 2019. In every jazz fan, there’s a little buffalo soldier; in Monty Alexander, there’s more than just a little. That’s why the Kingston, Jamaica born-and-raised jazz pianist has married the two sides of his musical soul on his latest album Wareika Hill, a reimagining of Thelonious Monk tunes through the lens of the music we most associate with Jamaica: Reggae.

The result is a sound Alexander has dubbed “Rastamonk Vibrations.” It swings, it grooves, and it may leave you searching for late-night snacks.

After growing up playing with Rastafarian musicians, then hearing and later meeting Monk when he moved to New York in the early sixties, Alexander concluded that Monk and Rasta were of one spirit. Alexander would later learn that when Monk first moved to New York from his native North Carolina, he lived in the neighborhood of San Juan Hill (now the area around Lincoln Center), which, at that time, was heavily populated by natives of the English-speaking islands of the Caribbean. For Alexander, that confirmed it: The island influences Alexander heard in Monk’s compositions were no coincidence.

And, indeed, if Wareika Hill proves anything, it’s that many of Monk’s most well-known compositions lend themselves nicely, and almost naturally, to the rhythms favored by the Rastafarians.

Take “Rhythm-a-ning,” which has always, to me, felt like the Monk tune most amenable to a reggae-style treatment. If you sense some Bob Marley influence in Alexander’s rendition, you’re on the right track. The arrangement here was influenced by Marley’s “Bend Down Low” and introduces itself with the musical equivalent of long dreadlocks before transitioning to a straight-ahead jazz sound that allows everyone to solo, most notably tenor saxophonist Wayne Escoffery, before reprising the opening reggae-jazz refrain.

Escoffery is also featured on a version of “Well, You Needn’t” recorded live at the Paris Philharmonie. The island influence here is perhaps a bit more subdued, but the calypso/dance hall rhythms are unmistakable. This one is played at a faster tempo than the album’s other version of the same tune, which was recorded in the studio. And no slight to the studio version, but the horns here—Escoffery on tenor and Andre Murchison on trombone—simply bring more energy, which is probably easier to summon when you’re playing before 2,600 Parisians in a packed auditorium.

Other A-list guests include tenor-man Joe Lovano (“Green Chimneys”) and one of Miles Davis’ favorites, guitarist John Scofield (“Bye-Ya”).

Alexander gives the latter what those in the reggae world call the “the rub-a-dub treatment,” a reference to the roots of modern dancehall music, the newer, more DJ-inspired form of reggae that began to gain popularity after Bob Marley’s death in the early eighties. The languid tempo, heavy bass line from Leon Duncan, and Ron Blake’s tenor invite us in for drinks and then Scofield injects a distortion-heavy guitar into the mix to make sure we stay put for a while. Somebody find me a hammock!

Meanwhile, “Green Chimneys” sees Joe Lovano given the first class introduction to Alexander’s Jamaica. Lovano reciprocates with a throaty tenor solo leading into extended improvisation from Alexander, during which he appears to slyly quote the first few notes of Marty Norman’s “James Bond Theme.”

Also of note is the “Bemsha Swing,” which transitions from roots-reggae to straight ahead jazz and then back again. Escoffery’s tenor playing here offers a real contrast in styles to Lovano’s on “Green Chimneys.”

The lone non-Monk tune is “Abide with Me,” a traditional Christian hymn that was a favorite of Alexander’s mother. It’s just Alexander at the piano, accompanied by a trio of Nyabinghi (Jamaican Rastafarian) drummers, here. Though neither composed nor played by Monk, this incredibly beautiful rendition of the folk hymn would almost certainly have resonated with his musical sensibility, for though Monk might be credited as a founder of bebop, he never really left the old traditions he came up with, and they never left him.