Larry McKenna, a tenor saxophonist with a sublimely beautiful, velvet-cloaked sound who was a mainstay of the Philadelphia jazz scene as both a player and an educator for more than six decades, died on Sunday at KeystoneCare Hospice in Wyndmoor, PA. He was 86.

His death was confirmed by his son, Matthew, who said he had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and congestive heart failure.

A lifelong Philadelphian, McKenna was the very definition of a local legend. Prior to moving into a Jenkintown apartment in his early 80s, McKenna had lived his entire life in just two houses, three blocks apart in the city’s Olney neighborhood. From this home base he performed and recorded with greats like Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Woody Herman, Shirley Scott and Clark Terry, and mentored generations of Philly musicians.

“Larry was the beginning,” says pianist Orrin Evans, who studied music theory with McKenna and later featured the saxophonist on his 2023 album The Red Door. “Not only the beginning, he was a constant. I wouldn't be doing any of this without people like Larry McKenna.”

Well into the 21st century, McKenna remained a living link to an earlier era of jazz, his understated style bridging the decades from swing through bebop to modernists like Wayne Shorter. His chief influences were legends like Stan Getz, Sonny Stitt, Lester Young and Illinois Jacquet, and while his own approach called back to those formative voices, he imbued his playing with such a soft-spoken directness that it maintained an emotional timelessness.

McKenna seemed to think in melody. His lines unfurled with an eloquent languor and a delicacy of expression that felt feather-light but conveyed an enveloping warmth. He possessed an encyclopedic knowledge of the American Songbook and communicated with those familiar tunes in the way that most of us speak words from a dictionary. I’ll never forget the unaccompanied rendition of “I’m Getting Sentimental Over You” that he played at the funeral for his lifelong friend Jimmy Amadie, in 2013: barely straying from the melody, he conveyed not just the heartbreak of Amadie’s loss but also the myriad facets of any decades-long friendship.

“You never wanted to play a melody with Larry,” says trumpeter Terell Stafford. “You would end up sounding like such an amateur trying to match his style, dignity and eloquence. When he started to take a solo, forget about it — it was almost like he wasn’t soloing, just writing a bunch of beautiful melodies that lasted chorus after chorus after chorus.”

Despite the reverence in which he was held in Philadelphia, McKenna remained largely a hometown secret for the bulk of his career. While music was his livelihood throughout his life, he didn’t release his debut album as a leader, My Shining Hour, until 1997, when he was 60. He followed that with the springtime-themed It Might As Well Be Spring in 2000, but remained under-recorded until a spate of late-life output beginning with Profile in 2009.

On From All Sides, he focused on original material for the first time, displaying his skills as composer, arranger and songwriter (on several pieces co-written with his friend, attorney and lyricist Melissa Gilstrap, and sung by Joanna Pascale). At the urging of drummer Dan Monaghan, saxophonist and arranger Jack St. Clair, and bassist Joe Plowman, he released World on a String, a gorgeous collection of standards and originals with strings, in 2023 — shortly before he was forced to take an extended hiatus from playing following a stroke.

Lawrence James McKenna was born on July 21, 1937, in Philadelphia, the youngest of four siblings. A sister, Patricia McKenna Bahner, of Powell, Ohio, survives him along with his son, Matthew, and a number of nieces and nephews. He was predeceased by another sister, Virginia McKenna Martin, and a brother, John Patrick McKenna.

After a brief dalliance with guitar as an adolescent, McKenna became enamored with the saxophone when his older brother brought home one of Norman Granz’s Jazz at the Philharmonic albums featuring Flip Phillips and Illinois Jacquet, both of whom became foundational influences. He signed up for sax lessons in high school, but lacking an instrument, was assigned a clarinet instead.

“They needed bodies out on the football field,” McKenna recalled in 2023, “so they put me in the band right away, even though I couldn’t play. I had a uniform before I could even make a sound.”

Largely self-taught, McKenna credited listening to icons like Getz and Charlie Parker for much of his education, though he studied briefly with a private teacher named Tony Bennett (no relation to the iconic singer he’d later accompany) and at the Granoff School of Music, whose alumni included John Coltrane, McCoy Tyner, Dizzy Gillespie and Pat Martino.

McKenna recalled frequenting Music City, the Center City music store that would host late-night sessions with noted musicians (famed as the site of Clifford Brown’s final Philly performance before his death, though the date remains contentious). He also attended workshops hosted by Camden DJ Tommy Roberts at North Philadelphia’s Heritage House, where touring artists would perform with and critique aspiring musicians. McKenna would nervously bring his tenor and test his mettle with the likes of Max Roach, Clifford Brown, Harold Land and Chet Baker, alongside fellow hopefuls including a young Lee Morgan.

That encounter, he later recalled, was one of the few instances in his early musical life where McKenna had the opportunity to interact with his African-American peers. In 2017, he and fellow Philly legend Bootsie Barnes celebrated their mutual 80th birthdays with a series of concerts and the release of their stellar co-led album The More I See You. In an interview at that time, they both marveled that despite having been regulars on the Philly scene since their earliest days, they didn’t actually meet until the 1980s.

“It wasn't a matter of choice,” McKenna said. “There were black neighborhoods and white neighborhoods, there was a white union and a black union, and you fell into wherever you were.”

During the late ‘50s, McKenna roomed for a time with Amadie, who was visiting New York City one day when he followed the sound of a big band into an upstairs room. He discovered clarinetist Woody Herman’s band in the midst of a combination rehearsal and audition. Fortuitously, the Herd was in need of both a pianist and a tenor saxophonist, so Amadie raced back to Philly and urged McKenna to return with him the following day. Upon hearing the saxophonist’s audition, pianist Nat Pierce asked if he was any relation to the pianist Dave McKenna. Larry said no, to which Pierce replied, “Oh, I guess all McKennas play good.”

“I thought, ‘I might have a chance of getting this job,’” McKenna continued. “It turned out that Jimmy and I both got the gig, and that Sunday we wound up going on the road.”

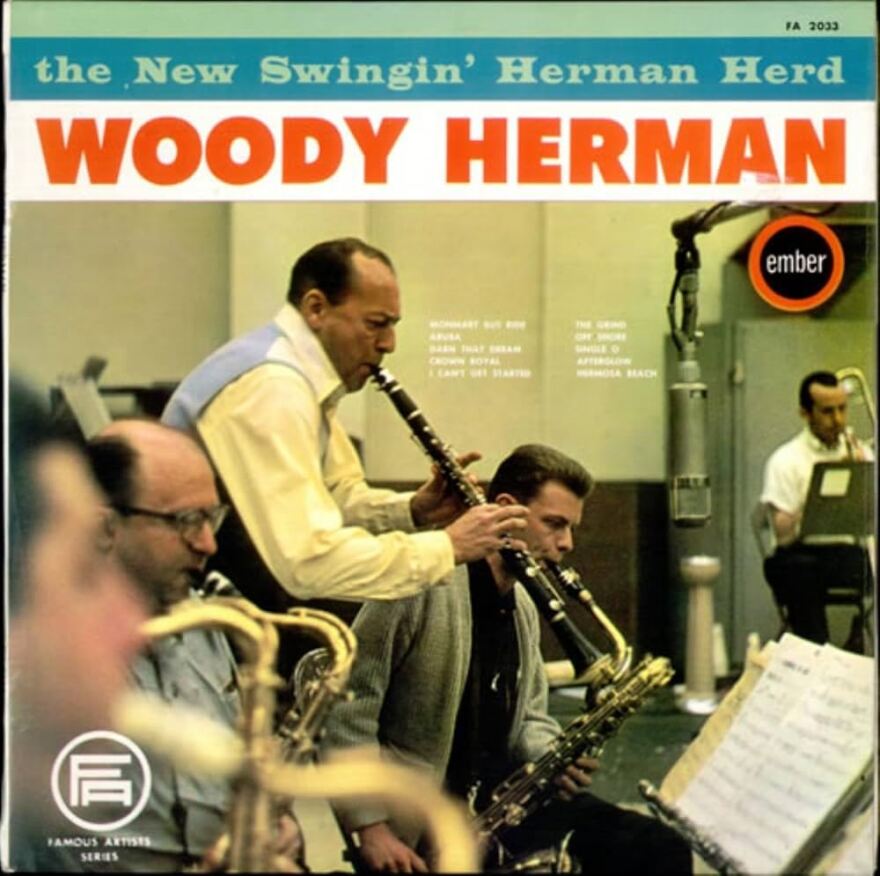

McKenna spent the next six months touring with Herman and recorded one album with the bandleader, 1960’s The New Swingin’ Herman Herd. (His face appears, blurred in extreme close-up, on the cover.) That series of one-nighters soured the young saxophonist on the idea of spending his life on the road, and with the exception of a brief, unsuccessful sojourn to the west coast, he spent the remainder of his career almost exclusively in the Philadelphia area.

He worked as a journeyman saxophonist for the next few decades, playing in wedding bands, in nightclub and big band gigs, and accompanying touring acts at now-defunct venues like the Latin Casino and Valley Forge Music Fair. In parallel he began his career as an educator, eventually teaching at Temple University, the University of the Arts, West Chester University, Widener University and the Community College of Philadelphia. He was also one of the invaluable mentors who taught by example on the stages of Chris’ Jazz Café and the storied jam sessions at Ortlieb’s Jazzhaus, along with such legends as Shirley Scott, Bootsie Barnes, Sid Simmons and Mickey Roker.

“I only took a couple of lessons with Larry, but right away it was like a massive light bulb went off,” recalls saxophonist Victor North. “I was having trouble relating to the old standards, and he helped put them into their original context. Suddenly the songs started coming alive to me. Generations of players have benefited from his knowledge and support. The warm spot under his wing is a very fertile learning ground.”

Faced with similar testimonials from countless younger players, McKenna routinely shrugged off the praise. “Larry always thought I was joking when I said he was my most influential teacher,” North says. “He would say, ‘Yeah right, because of those two lessons.’ Which is typical of his humility. He underestimated his effect on people.”

McKenna’s mild manner and humility were certainly reflected in his playing, but the embracing beauty, wit and compassion he was able to achieve revealed hidden depths. “He was soft-spoken, but when you got to know him he was brilliant and hilarious,” attests Monaghan, a student, collaborator and colleague of McKenna’s for more than 25 years.

“He was such a multi-dimensional guy for somebody who appeared so nonchalant and easygoing,” Monaghan adds. “You could easily say the same things about his playing. It was pretty and totally accessible, but the harder you looked, the more you realized the genius of it.”