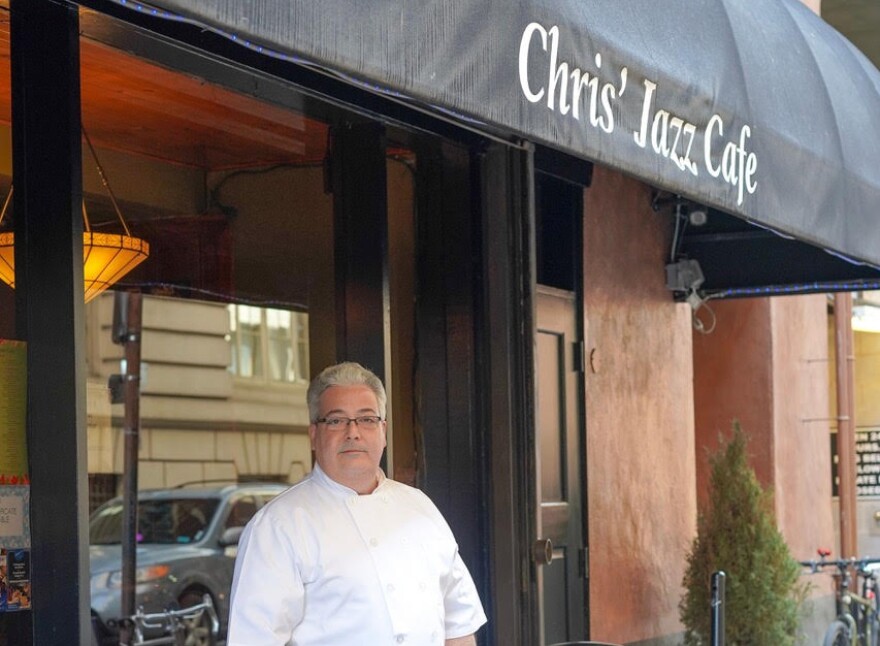

The past nine months have been a nightmare for independent live music venues, and the one that looms the largest in Philadelphia’s jazz community, Chris’ Jazz Café, hasn’t been spared.But early on Tuesday, December 22nd, industry pros like Mark DeNinno, Chris’ head chef and owner for the last 21 years, woke up to news of a potential lifeline. The long-awaited federal stimulus bill has passed through both houses of the Congress and is now awaiting President Trump’s signature.

Of the $900 billion of comprehensive aid approved, $15 billion will be allocated to independent entertainment venues like Chris’ and its peers as part of the Save Our Stages Act. That act allows venues like Chris’ to apply for grants through the Small Business Administration, which will then disburse funds of up to 45% of a venue’s revenue from 2019.

So, finally, there’s reason for optimism.

“This…money is what’s going to keep our industry open,” DeNinno told NBC10 Philadelphia Tuesday evening. “Without it, we would not be making it, and I know a lot of venues would not be able to make it.” Still, industry-wide, this optimism is of the cautious kind, primarily because time is of the essence.

“There are a lot of [independent local music venues] out there right now; they’re not going to make it two more months,” DeNinno told me minutes after speaking to NBC10. “If you haven’t had the ability to work with your landlord—and let’s face it that’s the biggest problem for all of us right now, our rent—you don’t have much time left for this money to come in. And so, we don’t want to see another 20% of the venues disappear in the next two months because this money took so long to get to us.”

It goes without saying that competition for consumers’ entertainment dollars is fierce; notice how DeNinno talks about the industry in terms of “us.”

How to Pivot Artfully: Livestream in the Short Term, Livestream in the Long Term

On Monday afternoon, DeNinno joined other local music industry leaders on a Zoom panel organized by Philadelphia City Councilman David Oh to commiserate, swap war stories, and share how they’ve attempted to adapt and hold on.

Among those on the panel with DeNinno was Sean Agnew. He was faced with the "Sophie’s choice" of having to permanently close his beloved local indie-rock stage and watering hole on South Broad Street, Boot and Saddle, earlier last month in order to save his larger venue, Spring Garden Street’s Union Transfer. At the time, Agnew, to the Inquirer, described the “double whammy” venue owners faced. It’s one DeNinno and others similarly situated have come to know too well.

“In addition to all the overhead costs [like building upkeep, utilities, insurance—and in Chris’ case the installation of state-of-the-art livestreaming technology] owners had to cover with next-to-zero revenue,” he told the Zoom panel, “there were also refunds to customers who’d purchased tickets to shows that were ultimately canceled.”

For DeNinno and crew, the hope was that Chris’ slickly and very competently produced livestream concert series, which went live in August, would at least temporarily staunch the flow of money leaving the business. A lot of money and man hours went into making Chris’ livestream competitive from a production-value standpoint. And it shows. The presentation is cinematic, downright Scorsesean compared to the single static camera experience to which music lovers, desperate for a concert-like experience, have become inured during these most unusual times.

Watch this video featuring the Orrin Evans Quartet, produced and recorded at Chris' in October, 2020

But, actually, this comparison isn’t apt at all, since these livestreams from Chris’—with enough cinematography technique to cover the first several weeks of Intro to Film—are produced much less like virtual concerts and much more like narrative documentaries or made-for-Hollywood musical biopics.

“We did work very hard at getting this put together, and Sean [Svadlenak], our production manager and audio engineer, has been instrumental in making sure that we are the benchmark in the industry for what we’re doing,” DeNinno said. “I think a lot of people think they’re going to put up a camera and do a livestream, whereas Sean said ‘we’re going to put up some cameras, and then we’re going to create art.”

DeNinno believes the high quality of their livestream presentation will be an appreciable post-pandemic asset for Chris’ in a less-prominent role, where it doesn’t have the pressure of being the home run hitter but can be a consistently valuable bat off the bench.

“We’re very optimistic that that market is going to develop for us,” DeNinno said, referring to the spike in livestream engagement he anticipates once audiences realize how distinct a user experience their digital product is and, somewhat ironically, once Chris’ returns to its primary business of being a live jazz club.

“We’ve seen a doubling of the numbers every month that we’ve been doing livestreaming,” he added. “So we think it’s going to be a big part of our future, and when we get back inside and actually have a full house of people, it’s just going to be the cherry on the top; it’s going to be additional revenues that will allow us to branch out and be even bigger than we are today.”

For now, a sanguine outlook for the future is just that; the viewers haven’t come yet, at least not to an extent that’s made a material difference to the bottom line.

“Because [the livestream’s] in its infancy right now, it’s really not generating enough money to pay the artists,” DeNinno told NBC10. “So we’ve set up a GoFundMe, where all of the money goes directly to our artists who perform and to the engineers who make the magic happen.”

That GoFundMe is slowly, but surely, chugging along, nearly $14,000 towards a goal of $50,000 at the time of this writing (around lunchtime on Wednesday, December 23rd). And DeNinno is grateful for the loyalty of Chris’ longtime clientele, from the dapper sophisticates to the regular bar-stoolies. But it’s been the musicians—as a group, hit harder by this pandemic than just about anyone— who’ve really shown him just how vital Chris’ is to Philadelphia’s jazz community.

Philadelphia’s Fraternal Order of Jazz Musicians

“One by one they started calling me and asking, ‘Mark, what does Chris’ need? Let us play a show for you. You don’t have to pay us; let the people pay you. It happened so organically that it really blew me away how much they loved the place.”

Over the last several weeks, Chris’ has hosted a steady slate of pay-what-you-wish livestream benefit concerts played by musicians on behalf of the club. Last Friday night, the young Juilliard-trained pianist and Chestnut Hill native Joe Block brought his trio up from NYC.

The next night, Mike Boone and his son Mekhi, the wunderkind teenage drummer, co-led their M&M Quintet with Neil Podgurski on piano, Elliot Bild on trumpet, and Adam Niewood on tenor saxophone. The preceding week saw performances by an Alex Claffy-led quartet featuring drummer Joe Farnsworth and trumpeter/vocalist Benny Benack III.

The Boones drove up from Wilmington; Block’s and Claffy’s bands drove up from New York. For Chris’, which is just another way of saying for each other…no sweat.

“When you spend years with people and you watch them grow up…,” DeNinno said, trailing off with some audible emotion. “I remember Alex Claffey,” he continued, this time laughing. “The first time he was on my stage, young and nervous and playing his first gig with his eyes closed.”

Now 28, Claffy has become one of the most in-demand bassists in New York City, releasing three records of his own and becoming a preferred sideman for A-listers like Orrin Evans, Randy Brecker, Joey DeFrancesco, Veronica Swift, and Kurt Rosenwinkel, the Philly-native guitarist with so many formative gigs at Chris’ who, even during his run as an international superstar, has always, in one form or another (more on that to come) found his way back to Chris’.

Claffy, meanwhile, originally from West Chester, wistfully recalls a typical Saturday night teenage routine of playing at the Clef Club, then walking over to Chris’ with his dream team cast of contemporaries like Justin Faulkner, Immanuel Wilkins, Dahi Devine, and Yesseh Furaha-Ali—all hoping to get a glimpse of the musicians they revered.

“We’d play over at the Clef Club all day until they’d close up the building, then we’d walk over to Chris’ and Justin [Faulker] would be telling us all about being on the road with Branford [Marsalis] because he was 16 and already in the big time,” recalled Claffy, laughing. “We’d walk by to see if we could sneak in because we were broke, and there were a lot of nights we couldn’t sneak in. But there were other nights we could. I remember seeing Orrin Evans’ band with [saxophonist] Stacy Dillard and Eric Revis and Nasheet Waits. That was the first night I ever met Stacy, and Stacy and I were just playing together last night. That was 13, 14 years ago.”

These stories of organic connections—sometimes endearingly engineered by enterprising young musicians—borne from nights at Chris’ that become lasting working relationships give credence to there being magic in the everyday. A lot of that magic, especially as it pertains to jazz music in Philadelphia, has occurred at Chris’ since Ortlieb’s Jazzhaus closed and re-branded in 2010.

“Chris’ really picked up the slack when Ortlieb’s shut down,” said bassist Mike Boone, the always opinionated, low-talking pied piper of Philadelphia’s best jazz jam sessions and the unofficial steward of Philadelphia’s legacy of on-the-bandstand jazz mentorship. “They totally did, and I give Mark [DeNinno] a lot of credit because he’s really a chef—he could be a five-star chef somewhere else. He could’ve gone another way, but thankfully he took to it and realized, ‘Oh, [expletive], Ortlieb’s isn’t here; there’s a void to fill here.’”

Even before Ortlieb’s closed as a traditional jazz venue, DeNinno, when deciding 21 years ago whether to take a shot with a jazz club, says he couldn’t just sit back and let the place close. “The former owners told me, ‘If you don’t take this over, this club’s going to die, and it won’t be here for generations to come.’ So I said, alright, sign me up. We stopped the bleeding and got it back on track. Four years later, we put in a stage and we ended up becoming Chris’.”

“And then, when the pandemic hit,” Boone added, “[DeNinno] saw a possibility and decided to invest. He took a long shot with the livestream and putting all that stuff in. Of course, when it happens live, in front of an audience, that’s where the real spirituality takes place. But the reality is the livestream is the new norm for now, and at least it’s allowed the musicians to get together and put our energies out into cyberspace.”

Necessity as the Mother of Invention

What Boone might not yet realize is that this livestream thing is slowly developing into something that’s a good deal more than just plugging in and sending the music out into the great unknown of cyberspace. DeNinno’s been so impressed with the product Svadlenak’s put out there that when Svadlenak proposed organizing an East Coast Virtual Jazz Festival, with Chris’ serving as one of the stages, DeNinno took the idea and ran with it, phoning his counterparts at Smalls and Birdland in New York, Blues Alley in D.C., and Scullers in Boston.

“They were all like, ‘That sounds like a great idea. How do we do it?’ And I said, ‘I don’t know; it’s the first time it’s ever happened, so we’re going to have to figure it out,’” said DeNinno laughing at how surreal it all is, especially because, as he’s fond of saying, he’s usually the guy “who’s in the rear with the gear.”

“But our initial meeting went very well. Everybody was very excited about it, and it looks like it’s going to be at the end of March where we’re going to be doing this virtual jazz festival with six different stages. This is something that’s going to happen, and it’s pretty exciting.”

Music Can Nourish the Soul, But Keep a Good Cook on Hand Just in Case

The cruel irony of musicians and music venues struggling right now is that it’s right now we need them most, in cynical times, where it’s easy to be short or petty with people, and there’s cause for frustration and so many are feeling bereft of spirit and existentially exhausted.

Sometimes it takes the manifestation of brilliance via music or the visual arts or athletics to restore one’s faith in humanity, to recognize that so much of what tests our spirit derives from society’s contrivances. But strip away those trappings, listen to Coltrane, watch Allen Iverson crossover, step back, then step over Tyronn Lue, and you rediscover the mind-bending truth that people, somehow, are naturally capable of the sublime. And when you see that, it restores your faith in a humanity that doesn’t always seem so good or even there at all, and it restores a sense of hope in yourself, for yourself.

Spiritual nourishment is, of course, one thing. But gastronomical gratification makes up a lot of what’s strengthened friendships between DeNinno and so many of the musicians who’ve played Chris’ over the past 21 years.

“Me being the chef, I love to cook for these guys,” says DeNinno crowing like a cross between a proud father and Paul Sorvino’s character from Goodfellas. “I always remember what they like, so I make sure that they have that when I see them on the schedule. Like, I’ll say ‘Oh, okay, [drummer and Philly native] Ari Hoenig’s coming in this weekend; I’ve got to make sure I’ve got crab cakes or crawfish because that’s what Ari’s going to expect from me.

“And then we sit down and enjoy ourselves together and we talk about our lives, our kids, our futures. We rarely ever talk about jazz and the jazz club because we’ve become such good friends over the years.

“So when [the musicians] turned around and said they wanted to [play benefit shows] shows for Chris’, my staff and I were taken aback. It was really something very special to me, and I was choked up a little bit when the amount of people started calling and saying ‘let us help, let us help.’”

One of those musicians who called and offered to help was Rosenwinkel. Thanks to the miracles of technology and the organizational wherewithal of vocalist JD Walter, it’s planned that Rosenwinkel, from Germany, will kick off a week-long virtual benefit to save the club so many Philly-rooted musicians think of as their own.

Many more musicians are expected to perform live from Chris’ stage, including but not limited to: Claffy, drummer Joe Farnsworth, vocalists Denise King and Walter himself, and Hoenig, whom I’m told should expect one of the better meals of crab cakes and crawfish he’s ever had. Unable to reach Walter, I’ve been told by those familiar with the planning that he’s reached out to several very high-profile, A-list names in the jazz world, and that the interest is there, that it’s a surprisingly easy sell to jazz musicians from elsewhere, so many of whom have a home club that treats them like family.

It’s why the Boones and Blocks and Claffys of the world will travel and play for a good meal and maybe a couple drinks (not for Mekhi, though—still too young) and tell their friends. It’s why Rosenwinkel will send his molecules from Germany through cyberspace.

Because, as several have told me, there’s a good chance that, but for Chris’, they’d be doing something different professionally.

“The kicker for me,” said Claffy, “was seeing Kurt Rosenwinkel at Chris’ with Kendrick Scott, Aaron Parks, and Joe Martin. It was incredible music, just transcendent—like seeing Coltrane or someone like that. And I saw that concert and remember saying ‘I want to play with that guy.’”

About six or seven years later, Claffy got his wish—after the two were connected by Orrin Evans, who first noticed Claffy, you guessed it, at Chris’.

If the streaming gods allow and the Wi-Fi proves hardy, maybe this mid-January star-studded benefit for Chris’ sees Rosenwinkel and Claffy share a virtual stage so many years after the former inspired the latter from Chris’ physical one. Stranger things have happened this year.